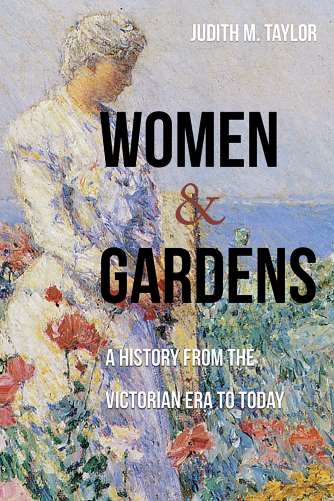

In the book Women and Gardens: A History From the Victorian Era To Today, published by University of New Mexico Press, the author Judith M. Taylor offers a groundbreaking exploration of women’s essential yet often overlooked contributions to horticulture and garden design. Spanning more than two centuries, Taylor uncovers the stories of women whose hands shaped not only plants and landscapes, but also cultural history itself.

The book begins by describing Obstacles that historically barred women from gardening as a serious or professional pursuit. This exclusion mirrored the broader marginalisation of women, whose labour was dismissed or left undocumented by a male-dominated historical record. Taylor shows how women, regarded as less than fully adult by those in power, faced countless barriers to recognition.

credit the Trustees of the British Museum

credit the City of Victoria Archive, Victoria, British Columbia

In discussing Women Gardeners in the Eighteenth Century, Taylor highlights early female figures who, through domestic and often unpaid efforts, laid critical groundwork. These women transformed kitchen gardens and ornamental plots into thriving spaces of creativity and skill, despite having their achievements ignored by mainstream histories.

Through Opportunities, Taylor describes how shifting attitudes, educational changes, and a growing nursery trade in the nineteenth century began to open new paths for women. These hard-won opportunities planted the seeds for later progress in horticulture and design.

Gardening itself became a symbol of freedom and personal agency, as shown in Gardening as Liberation. For many women, tending a garden was more than a pastime — it was an act of independence and a way to claim space and authority in a world that denied them both.

credit the Regents of the University of California

Taylor explores the rise of Horticultural Education for Women, showing how access to formal training helped women advance from informal garden keepers to respected professionals. These educational gains laid a foundation for female experts to emerge in their own right.

In Women in Garden and Landscape Design, Taylor documents how women increasingly shaped large-scale landscapes, from urban parks to private estates. Their vision challenged assumptions that only men could lead in landscape design and planning.

Women in Ornamental Plant Breeding honours the important but under-recognised role women played in developing new varieties of flowers and ornamentals. Their creative innovations influenced entire plant industries and left a lasting legacy in horticulture.

Finally, Gardens as Symbols in Women’s Writing explores how gardens became powerful metaphors in literature, expressing women’s struggles, dreams, and acts of resistance.

Taylor’s book is far more than a horticultural history — it is a restoration of voices silenced or ignored for centuries. She challenges the old adage that “history is written by the victors,” showing how women’s work in gardening was systematically left out of the record. Today, with women outnumbering men in landscape design, Women and Gardens is timely and necessary.

This compelling, beautifully researched volume is essential reading for anyone interested in history, gender studies, or the transformative power of gardens.