At the Musée Marmottan Monet in Paris, France, the latest edition of “Dialogues Inattendus” draws to a close, leaving visitors with a powerful reflection on the resonance between past and present in art. This ninth chapter of the series, which invites contemporary artists to engage directly with the museum’s collections, has been devoted to Françoise Pétrovitch and her dialogue with Berthe Morisot. Entitled “Soleil”, the exhibition has illuminated the unexpected intersections between two women painters separated by more than a century, yet united by their exploration of intimacy, nature, and the subtle power of gesture.

Since 2019, the “Dialogues Inattendus” program has offered a fresh perspective on the museum’s holdings, bridging Impressionist heritage with the visions of contemporary artists. Françoise Pétrovitch, one of France’s most celebrated contemporary figures, was a natural choice. Known for her versatility across drawing, painting, sculpture, ceramics, and scenography, Pétrovitch creates work that balances tenderness and unease, quiet intimacy and monumental presence. Her art often portrays adolescents, dreamlike hybrids, and suspended moments of vulnerability. For this exhibition, she turned toward nature, a theme that has always been latent in her practice, to enter into conversation with Morisot, one of the great pioneers of Impressionism.

credit Studio Christian Baraja SLB

credit Studio Christian Baraja SLB

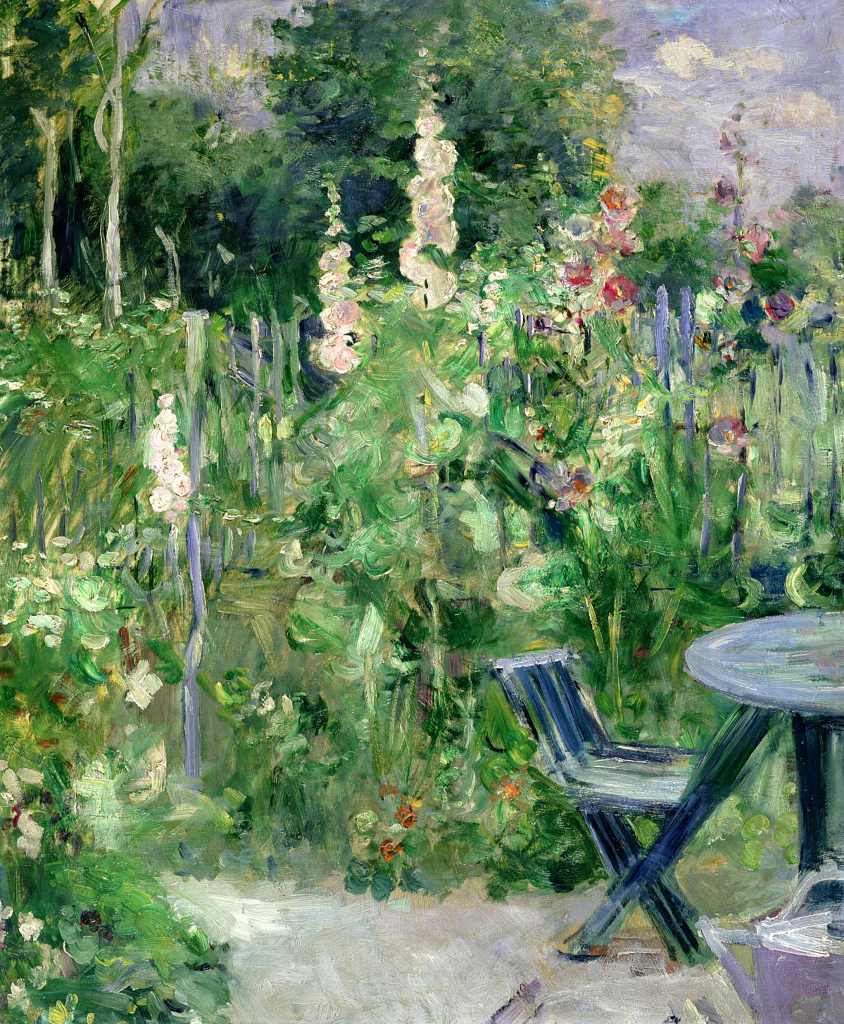

At the heart of the exchange are two works: Morisot’s Roses trémières (1884) and Pétrovitch’s recent series Soleils (2024). While Morisot captured the elusive vitality of hollyhocks in a garden scene filled with fragments, half a chair, part of a watering can, a glimpse of fence, Pétrovitch responded with large ink washes of sunflowers, monumental and raw. In her own words, the dialogue is not about similarity but divergence: Morisot used bleached tones and diffused light, while Pétrovitch avoids white almost entirely, opting for depth and saturation. Together, their works form a garden that expands across time and space, where roses and sunflowers seem to bloom side by side.

Beyond the formal contrast, the exhibition raises broader questions of visibility and recognition. Morisot, despite her central role in the Impressionist movement, had “without profession” recorded on her death certificate, a striking reminder of how women artists were marginalised. Pétrovitch’s choice to engage with Morisot was both artistic and political: an act of recognition, dialogue, and continuation. Her portraits of sunflowers are not only botanical but also metaphorical, embodying resilience, fragility, and cycles of growth.

The staging at the Marmottan Monet amplified this interplay. Visitors moved between Morisot’s luminous fragments and Pétrovitch’s towering blossoms, experiencing the sensation of passing from one garden to another. The effect was immersive yet contemplative, reinforcing the idea of art as a continuous conversation across generations.

As the exhibition concludes, it leaves behind a resonance that lingers beyond the museum walls. By pairing Morisot and Pétrovitch, “Soleil” did more than juxtapose two painters; it created a space where questions of memory, gender, and representation were woven into the timeless rhythms of nature. In doing so, it reaffirmed the power of the “Dialogues Inattendus” series: to remind us that the past is never closed, but always available for reawakening through the eyes of today’s artists.