Copenhagen, in Denmark is increasingly recognized as a paradigmatic case for the integration of landscape architecture, cultural heritage, and sustainable urbanism. The city functions as a living laboratory where historic precedents, modern cultural landscapes, and experimental ecological infrastructures are continuously reinterpreted. Traversing the city from its center outward reveals a chronological layering of design approaches, from Renaissance formality to contemporary multifunctional infrastructures.

The itinerary begins in the King’s Garden, established in the early seventeenth century around Rosenborg Castle for King Christian IV. Conceived in the Renaissance tradition of axial planning and ornamental display, it remains a crucial precedent for the integration of aristocratic symbolism and public accessibility. Nearby, the nineteenth-century Botanical Garden, designed by landscape architect H.A. Flindt in 1874, illustrates the scientific and educational role of landscape. Its Palm House, nowadays on renovation, built by Peter Christian Bønecke in 1874, demonstrates Victorian engineering while producing a controlled microclimate that mediates between global plant collections and local public experience.

Within walking distance, the Cinematheque rooftop terrace, Filmtaget, designed as part of the Danish Film Institute’s headquarters by Dissing+Weitling, provides a vantage point from which to understand urban green continuity. The panoramic view across the Parkmuseerne district reveals how the King’s Garden, the Botanical Garden, and Østre Anlæg together generate a connected green fabric in the city center.

Proceeding south, the Royal Library Gardens, designed in 1920 by Jens Peder Andersen with architect Thorvald Jørgensen, represent interwar landscape design principles. Westward, Tivoli Gardens, founded in 1843 by Georg Carstensen, epitomize the role of landscape in leisure, while the adjacent Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, commissioned by brewer Carl Jacobsen and designed by architect Vilhelm Dahlerup, demonstrates the cultural potential of interior landscapes—its Winter Garden remains a masterpiece of late 19th-century glass architecture.

Crossing the harbor, Opera Park is a recent project by the Danish architecture office Cobe, completed in 2023. The park integrates six themed landscapes with rainwater harvesting, permeable surfaces, and solar systems. Biodiversity, climate adaptation, and visitor experience are conceived as interdependent, positioning the park as a model of resilient landscape design.

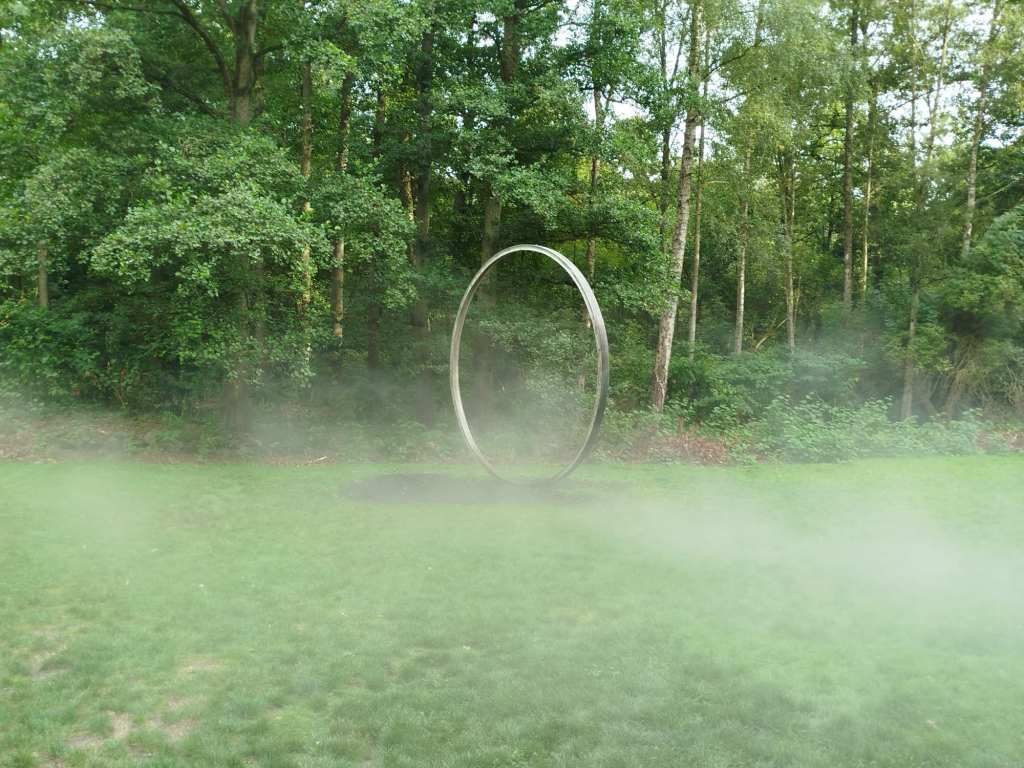

Further north, the Ordrupgaard Museum, originally designed by Gotfred Tvede (1918), has been expanded by Zaha Hadid Architects (2005) and Snøhetta (2021). The museum’s sculpture park and exhibitions such as Plant Fever foreground the cultural significance of plant life. Nearby, BaseCamp Lyngby, designed by Lars Gitz Architects (2021), extends ecological thinking into architecture. Its undulating green roof regulates temperature, retains water, and creates habitats while functioning as a social space.

In Østerbro, ØsterGro rooftop farm (2014), founded by urban farmers Kristian Skaarup, Livia Urban, and Signe Wenneberg, illustrates adaptive reuse and productive landscapes. By converting a former car-auction house into a 600 m² agricultural roof, it demonstrates the role of design in linking ecological habitat, social infrastructure, and gastronomy, particularly through its restaurant Gro Spiseri.

Returning toward the inner harbor, the new Noma restaurant (2018), designed by BIG – Bjarke Ingels Group with landscape design by Piet Oudolf, demonstrates cross-disciplinary collaboration. Oudolf’s naturalistic perennial planting evolves annually in dialogue with the chefs, transforming the site into a living experiment between gastronomy and landscape.

credit Giuseppe Liverino

The itinerary culminates at CopenHill (Amager Bakke), completed in 2019 by BIG – Bjarke Ingels Group with landscape input from SLA Architects. Beyond its technological function, converting 440,000 tons of waste annually into clean energy for 150,000 homes, it performs as a multifunctional urban mountain with ski slopes, climbing walls, and a biodiverse green roof. CopenHill exemplifies infrastructure as landscape: a hybrid typology where ecological, recreational, and industrial systems operate in synergy.

Taken together, these sites articulate a coherent narrative of Copenhagen’s landscape development and the city demonstrates how design can serve simultaneously as heritage conservation, ecological adaptation, and cultural innovation. Copenhagen offers not merely exemplary case studies but a methodological framework: one in which landscape is understood as an active system that sustains urban life, mediates between past and future, and redefines the relationship between people, place, and ecology.