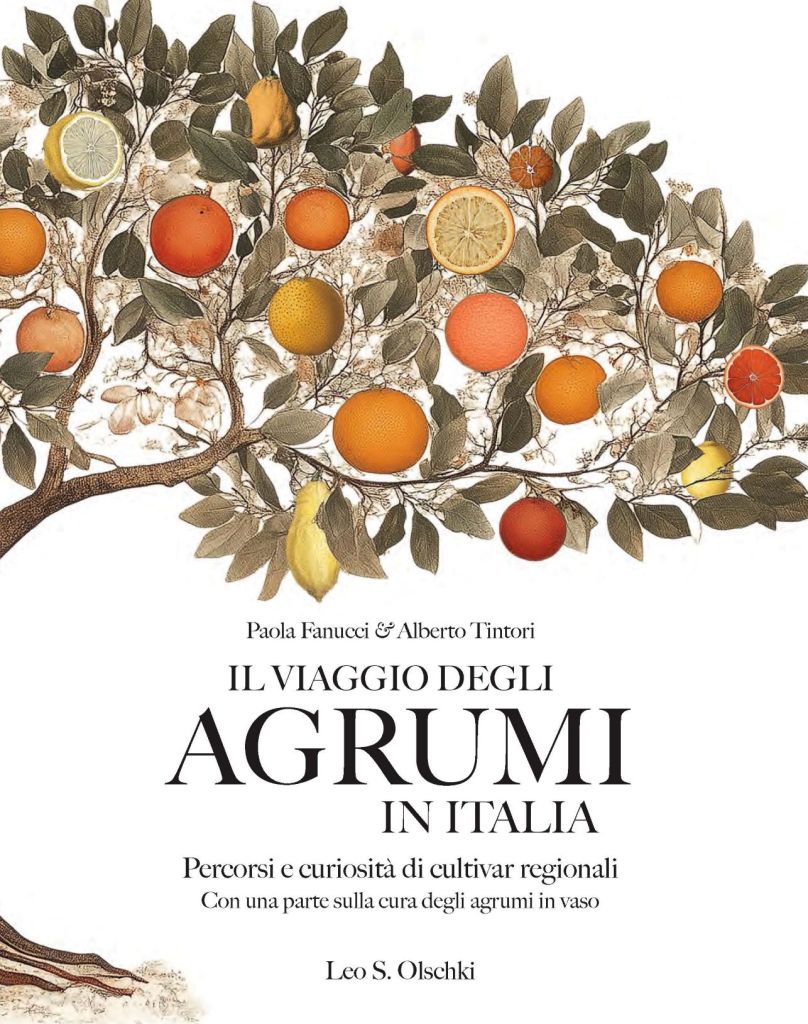

The book ‘Il viaggio degli agrumi in Italia. Percorsi e curiosità di cultivar regionali. Con una parte sulla cura degli agrumi in vaso‘ (The Journey of Citrus in Italy: paths and curiosities of regional cultivars, with a section on growing Citrus in pots) by the authors Paola Fanucci and Alberto Tintori, published by Leo S. Olschki Publisher, and available in german language too, is not just a botanical study, but a cultural and historical exploration of one of Italy’s most symbolic agricultural treasures: citrus fruits. Part of the Giardini e paesaggio series, vol. 60, the book blends scholarship with storytelling, offering a portrait of how oranges, lemons, mandarins, and other citrus varieties have shaped both landscapes and traditions across the Italian peninsula.

From the very first pages, the authors set a reflective and evocative tone: the scent of orange blossoms or the taste of lemon peel are described as sensory gateways to memory and identity. Such an introduction prepares the reader for a journey that is at once intimate and scholarly, in which the story of citrus fruits is interwoven with the story of people, places, and centuries of cultivation.

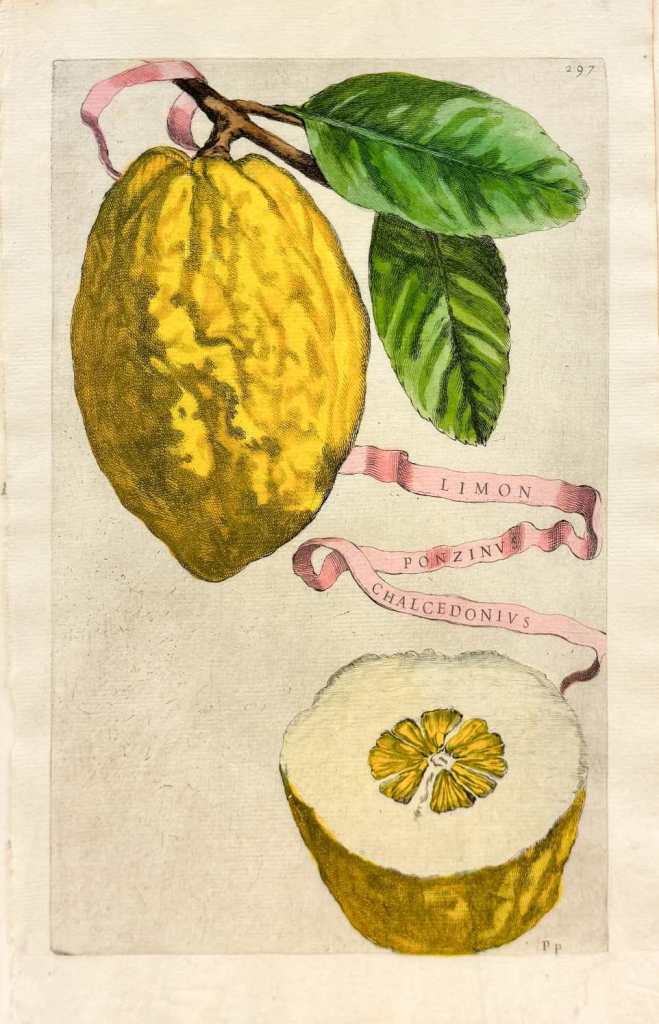

The book begins with a historical overview, tracing the mythic and real roots of citrus cultivation. References to Giovan Battista Ferrari’s 1646 Hesperides, Pierre Laszlo’s chemical history of citrus, and Giuseppe Barbera’s recent botanical studies highlight the long-standing fascination these fruits have exerted on scientists, gardeners, and writers. Yet Fanucci and Tintori distinguish themselves by turning their gaze specifically to Italy, exploring how citrus fruits became embedded in the cultural and economic fabric of distinct regions.

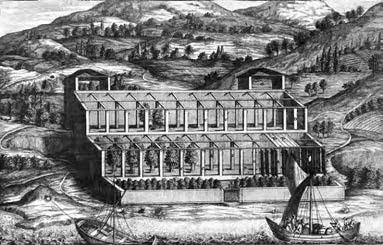

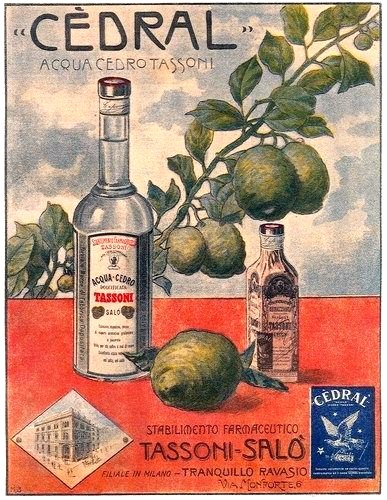

The core of the book is a regional journey across Italy’s citrus landscapes. Through meticulous research, archival documents, agronomic treatises, works of art, travelers’ accounts, the authors reconstruct the pathways by which different cultivars arrived, adapted, and transformed territories. Their analysis brings out how cultivation was not just agricultural practice but also a driver of economy, architecture, and social life: terraces and stone walls reshaping the countryside, trade routes opening markets, women’s labor sustaining entire production cycles, and local rituals and cuisines incorporating these fruits into daily life.

Equally fascinating is the book’s attention to biodiversity. The survival of rare and local cultivars, preserved thanks to the persistence of farmers and enthusiasts, is presented as both a scientific treasure and a cultural legacy. By cataloguing this “citrus biodiversity,” the authors invite readers to consider conservation not merely as an ecological duty but as a way of safeguarding collective memory.

A particularly useful feature for gardeners and enthusiasts is the practical section devoted to citrus cultivation in pots. Here, the authors move from history to hands-on guidance, outlining techniques of care, soil, and pruning, alongside innovative approaches to biological pest control developed through years of experimentation. This section grounds the book in the present and makes it accessible beyond academic circles, appealing to those who may want to grow their own “golden apples” on balconies and terraces.