In Literary Gardens book, author Sandra Lawrence and illustrator Lucille Clerc invite readers to wander through fifty of literature’s most evocative green spaces: a journey that proves as rich, strange, and varied as the stories that created them. Gardens, as Lawrence reminds us, are never just backdrops. They are portals, emotional barometers, stages for revelation and transformation. Her new book, published by Frances Lincoln, celebrates these spaces with lyrical precision and scholarly curiosity, while Clerc’s illustrations lend the volume a sense of dreamy immersion. Together, they offer a compendium of literary landscapes that feel both familiar and newly enchanted.

credit Lucille Clerc

credit Lucille Clerc

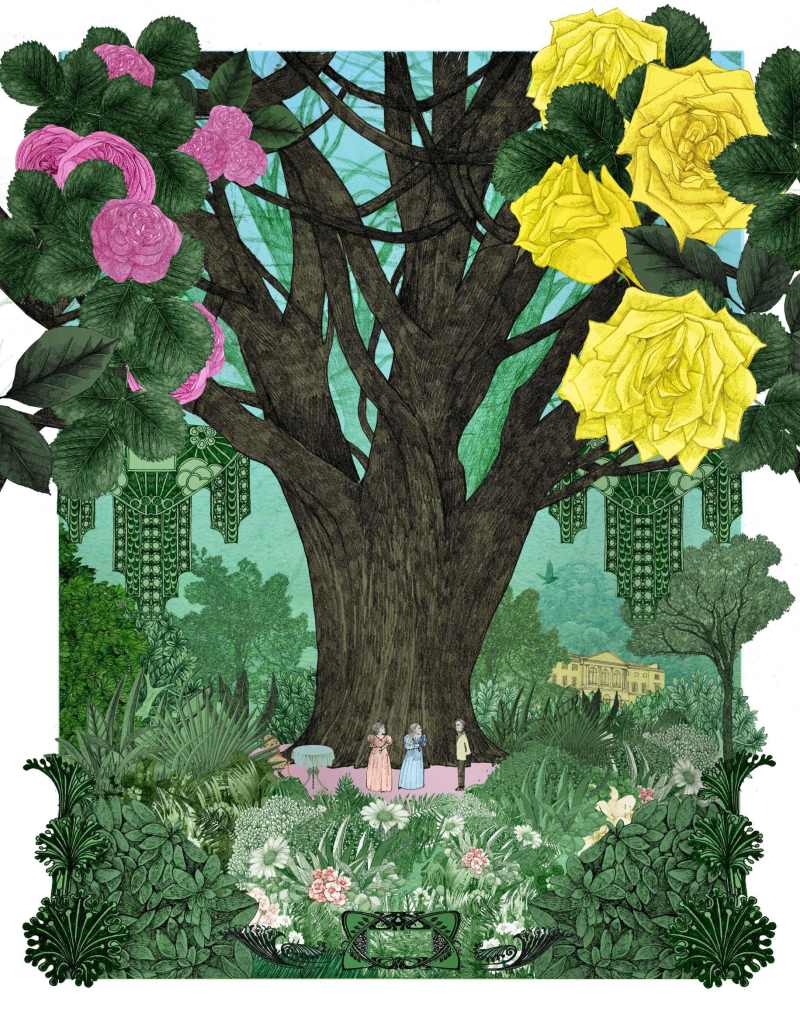

Drawing from a remarkably wide-ranging canon, Literary Gardens bridges centuries, genres, and traditions. Classic childhood refuges appear alongside darker, more ambiguous terrains. Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Secret Garden opens its gates once again, its promise of renewal juxtaposed with the disorienting strangeness of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Sandra Cisneros’s The House on Mango Street stands comfortably beside the mythic grandeur of the Rāmāyaṇa; Jorge Luis Borges’s metaphysical maze in “The Garden of Forking Paths” complicates notions of space and choice, while Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep reminds us that gardens can conceal as much as they reveal.

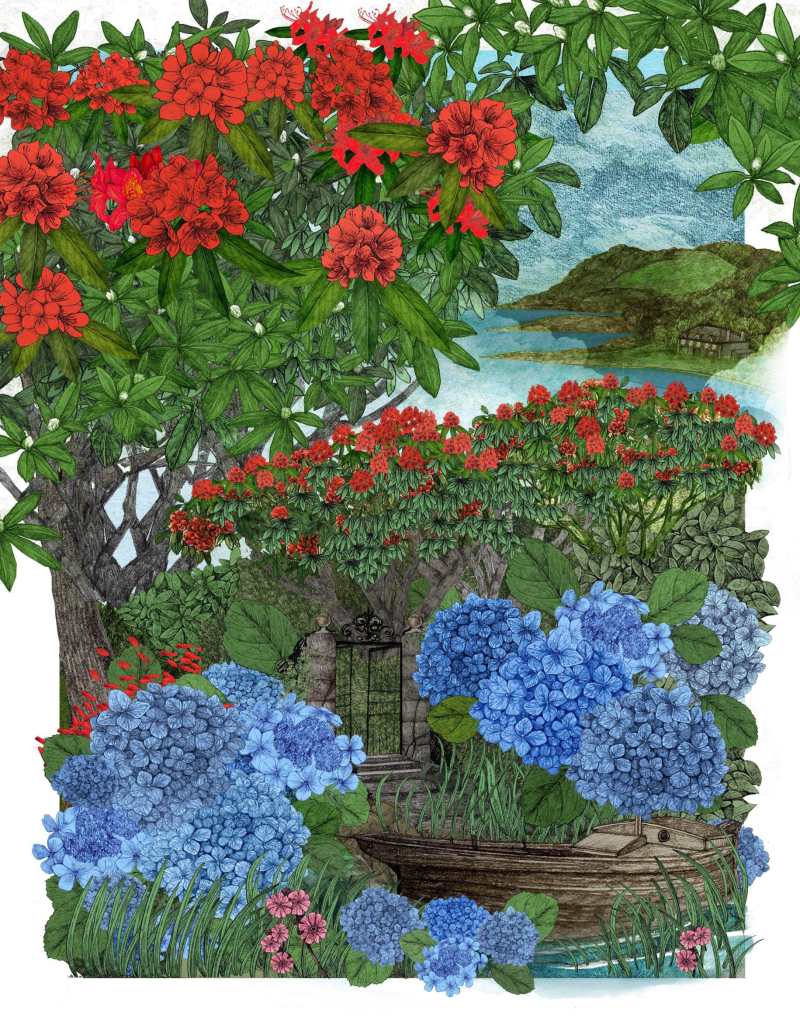

The selection highlights the emotional elasticity of gardens in fiction. They can be loci of innocence, as in Beatrix Potter’s mischievous The Tale of Peter Rabbit, or engines of suspense, as in Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca, where carefully tended grounds mirror secrets tightly pruned. In Giorgio Bassani’s The Garden of the Finzi-Continis, the garden becomes a sanctuary both intimate and doomed. And in Patrick White’s The Hanging Garden, it becomes a site of exile—lush yet unsettling.

credit Lucille Clerc

Frances Hodgson Burnett

credit Lucille Clerc

credit Lucille Clerc

Lawrence’s commentary, shaped by her long career writing about gardens for major publications and her deep interest in the fantasies they inspire, brings coherence to this eclectic constellation of texts. She traces how these spaces embody longing, danger, nostalgia, or transcendence. Some entries draw out the mystical, Terry Pratchett’s Mort or the world tree imagery, while others highlight the mundane yet magical, such as Sei Shōnagon’s attentive nature observations in The Pillow Book or Elizabeth von Arnim’s humorous self-portrait in Elizabeth and Her German Garden.

Clerc’s illustrations complement Lawrence’s prose with sensitivity. Known for her intricate depictions of natural forms and urban architecture, Clerc transforms each garden into a dreamlike tableau without sacrificing specificity. Her visuals guide readers not simply to look at these gardens but to inhabit them-shadowed corners, wild borders, and all.

What ultimately distinguishes Literary Gardens is its understanding that fictional gardens endure because they live beyond the page. They become the landscapes of our own memories and imaginations. Whether exploring the spiraling possibilities of Borges, the moral complexities of Hawthorne’s “Rappaccini’s Daughter,” or the whimsical impossibilities of Narnia, this book cultivates a renewed appreciation for literary spaces that linger long after reading.